The world of brewing and distilling is awash with characters of character and replete with stories of Odyssean successes and seemingly Sisyphean struggles to stay on top of the market pack. Just like any industry there are winners and losers, booms and busts. Starting a brewery or distillery can be incredibly rewarding, but it isn’t without its risks.

In an effort to mitigate some of those risks and take advantage of growing market trends, some industrious business owners have begun to double dip into both distilling and brewing under the same roof. These hybrid operations, often referred to as brew-stilleries, offer a lot of opportunities for growth, marketing, and synergy if done properly.

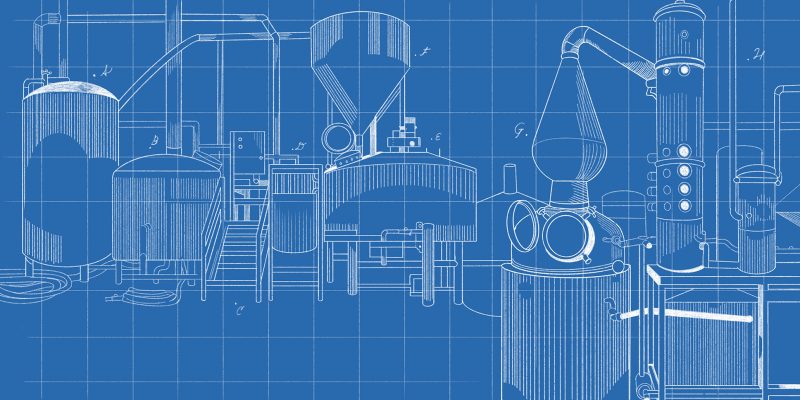

Beer and many styles of spirits (whisky, most vodkas and gins) share a lot of the same DNA in their production processes. Start with a grain, mill it, mash it, boil then cool the wort and then ferment the sweet liquid to produce alcohol. In brewing, the newly fermented beer is then put through various conditioning, filtration, and packaging operations while in distillation the beer is put into a still to be transformed into spirit. That spirit can then be matured in casks, or if distilled to a high level of neutrality, converted into vodka, gin, or liqueurs.

If an existing brewery has a simple mash tun and fermenters, it could in theory simply mash grain in their mash vessel, omit the boiling step, and ferment as usual. Now add a decent still to the mix and they can produce spirits from their brewing equipment with relatively minor changes to their approach and technique.

Of course, this scenario only really works if the brewery plans on producing primarily with malted barley. Single malt whiskies can be produced this way with comparative ease. However, if the company is looking to work with high amounts of unmalted grains for its spirits, then they may need to add a cereal cooker to their production kit. This would allow them to make whiskies such as bourbons and ryes. They could also produce rum and other spirit categories quite easily with such a system.

A few caveats are worth mentioning at this point, however. First, distillation is highly energy intensive. The stills and the cereal cooker require immense amounts of heat energy. So, a company may need to look at whether their brewery has the utility capabilities to supply the necessary amounts of energy to these vessels alongside their normal brewery activities. In nearly all cases, this heat energy needs to eventually be removed from the system, which means the facility will likely need an increase in cooling abilities. Second, distillation really is its own skillset. It is possible to train brewers to do the job, but most people opt for hiring an experienced distiller. Finally, (and in some cases most importantly) the brewery needs to assess whether their infrastructure has the ability to handle large amounts of high abv alcohol. Local fire codes will come heavily into play here the brewery owners should discuss this with their local agency. However, it should be noted that in many instances, distillery production areas are often rated as Class 1 Division 1 meaning there are high levels of ignitable liquids and vapors hanging around for long periods of time. This may have a dramatic impact on building materials and equipment purchases for the interested brewery.

Despite the expense of equipment and probable labor outlays, a growing number of companies are seeing the benefits of dipping their toes into both production streams. Erik Owens, President of the American Distilling Institute, says that their organization currently has 156 American members and 209 International members that fit into the brew-stillery category. However, he is quick to point out that the real number is likely somewhat higher as some companies will often fail to mention that they have a brewery onsite as well, since ADI is a distillery trade body. Erik expects these numbers to continue to grow in the next few years as more people become attracted to the idea of producing both beer and spirits under one roof.

The concept of the brew-stillery isn’t exactly new. Many famous craft breweries in North America have added distillation to their programs over the years. Some standout names include Dogfish Head in Rehoboth Beach, Deleware, Rogue in Newport Oregon, and New Holland in Michigan. Anchor Brewing in San Francisco also started a distillery in the 1990’s, though the company has now separated the two enterprises with the sale of Anchor Brewing to Japan’s Sapporo a few years ago. (The distillery now operates on its own and has been renamed Hotaling and Co.)

And while perhaps the most common scenario is of a brewery deciding to get into distilling, the industry is also seeing the occasional distillery dreaming of producing their own suds. One such enterprise is Menaud in Clermont, Quebec. This award-winning operation started a few years ago with the intent of making world class vodka and gin. Menaud’s VP of Marketing, Charles Boissoneau, says that it didn’t take long for the company to begin thinking about making beer as well. They took baby steps toward their brewing ambitions by starting with a single barrel (bbl) system for the first year to test recipes and the concept. From that nano-sized pilot system they then scaled up to a healthy (and more commercially viable) 1,500-liter mash tun linked to several 4,000-liter fermenters. Charles says that the business is currently an even split between their spirits portfolio and beer, but something else the company has been working on is quickly gaining traction with customers: Ready to Drink (RTDs).

RTDs or Ready to Drink cocktails have taken the world by storm. The RTD category is pretty broad and includes everything from actual cocktails to wine spritzers to hard seltzers (which itself includes the commercial juggernauts, White Claw and Truly). The category has been explosive in its growth, particularly in the United States, however, sales are rapidly growing across the globe. In the U.S. RTDs are now second only to wine for most valuable alcoholic beverage category. In 2020, the RTD segment in the U.S. grew 62.3% in volume. Of that volume, hard seltzers made up the vast majority of growth with a jaw-dropping 130% increase from 2019. However, canned cocktails and long drinks shouldn’t be discounted. While making up only less than 10% of the RTD market, sales volume of these beverages still grew 52.7% in 2020.

So, why all the talk of RTDs? Well, breweries may already have easy access to a canning line either in-house or through localized mobile units. And if they are interested in starting a distillery, there are a wealth of options for using their spirits in canned (or sometimes bottled) RTDs. Gin and Tonics, Vodka Sodas, Whiskey Highballs and so much more are simple to produce and package with a distillery and adjacent canning line.

RTDs aren’t the only way to work some synergy into the brew-stillery design. How about diverting some of the (unhopped) wort stream from some of the flagship beers into the distillery and producing whiskey? This is exactly what Rogue Ales did with their esteemed Dead Guy Ale. They simply used some of the Dead Guy wort, fermented it and distilled it into Dead Guy Whiskey. Then for added fun, take those whiskey barrels and use them to age some beer. (The company can then use the beer barrels for some of its whiskey as well for even more clever product line extensions.)

Certainly, with an increasing emphasis and post-lockdown demand for brewery and distillery tourism, many companies have looked to their tasting rooms for added revenue streams. Having a brewery and distillery on-site allows for a wider variety of beverage choices to offer customers. Some people don’t dig beer and prefer spirits and vice versa. The brew-stillery allows a company to cast a wider consumer net than either business type could do on its own.

In fact, sometimes local regulations may require companies to do such things if they want to be able to serve beer and spirits in their tasting room. The highly acclaimed Texas distillery, Balcones, recently added a small on-site brewery to slake the thirsts of their more beer savvy patrons. The beer is not meant for sale outside the tasting room, just for customers coming in with their beer-loving friends.

One of the most interesting case studies of the brew-stillery format is that of Rogue Ales and Spirits in Newport, Oregon. Rogue started their brewing adventures in the late 1980’s rapidly gaining a loyal consumer base and racking up countless awards along the way. Steve Garrett, Rogues VP of Business Development recounts the company’s humble distillery beginnings. “We started distilling in 2003 in a little room on the second story of our pub in downtown Portland, this was before the idea of craft distilling was popularized and there were only a few others around the country doing it. For us it was like most things we do, a pursuit of curiosity, answering the question “what if?” and just continuing to push boundaries. Distilling is a natural progression of what we do on the beer side, because to make a spirit you have to essentially brew a beer first before distilling. We thought if we can make great tasting craft beer with high quality ingredients and a sense of origin, why not go one step further and distill as well. It made a lot of sense to us that people would be looking for the same attributes that make craft beer so popular in their spirits as well.”

Since those early years, Garrett says that their spirits division has grown considerably. Their spirits portfolio now makes up about 15% of their business with the division seeing a massive 150% upshot in growth during 2020.

Despite the successes, Garrett points out that it hasn’t always been easy. He says, “Launching a distillery was time-consuming and there were added expenses, but breweries and distilleries require a lot of similar skills so the brew-stillery model was a natural progression. We’re also primarily known as being one of the first microbreweries so spreading the word that we’re also a distillery that makes quality, world-class spirits was a bit of a challenge. It took time and energy to build up our reputation and brand recognition on the spirit’s front.”

This is all to say that people planning on pursuing the brew-stillery model, should do their homework. Interested parties should talk with people from both sides of the industry, hear their stories and get their input. They should also realize that while there is the potential for a lot of synergy between the two operations, there are also a lot of important differences regarding regulations , processes, market cues, and necessary skillsets. However, if the company has done their research and has knowledgeable people at their side, the brew-stillery model can be immensely rewarding. Consumers love choice and the brew-stillery offers that in spades.

Matt Strickland is the Head Distiller at Distillerie Côte des Saints and Senior Advisor, Distillery Technical Services at First Key Consulting.