It has become almost a cliché for those in the brewing industry to reflect on the mindset of a shopper standing in front of the modern beer aisle, trying to take in all the available choices. Just five decades ago, after all, a would-be beer purchaser would find his or her selection more limited, with his options consisting of…well, essentially just beer. Choices in terms of styles were almost non-existent, other than a few sporadically distributed malt liquor brands. Then came light beer, and craft beer, and the many styles of craft beer, and the segmentation revolution was soon underway.

Today that revolution is making a quantum leap forward, as brewers increasingly expand into beverages that don’t meet the traditional definition of beer. Hard ciders, hard teas, hard kombucha, ready-to-drinks (RTDs) based on spirits or wine or malt, and of course hard seltzers. In fact, less than a decade after their introduction hard seltzers are already fragmenting into subcategories: CBD-infused, lemonade hard seltzers, seltzers with health-inspired ingredients like probiotics or electrolytes – and now, ranch water. And non-alcohol options continue to grow in relevance in brewers’ portfolios.

It is the era of microsegmentation. Of drinks, of occasions, and maybe of consumers.

What underlying dynamics have changed to spark this revolution? It’`s a matter of faith that today’s drinkers are far more variety-driven and far less habit-driven than their predecessors, and this is certainly true. But maybe the evolution of the drinker’s mindset isn’t the only driver of this new reality. There may well have been “explorer-type” drinkers in 1970 who simply did not have the opportunity to express their demand for variety because there was so little supply of variety. What has changed may well be brewers’ and other producers’ willingness to invest in microsegments, and then be patient as they waited for a payoff from that investment.

A lot of new category introductions have failed over the decades, and they’ve frequently been dismissed as fads in hindsight. Wine coolers were a thing, and then they weren’t a thing; almost no-one doubts that hard root beer, and hard soda in general, was a fad.

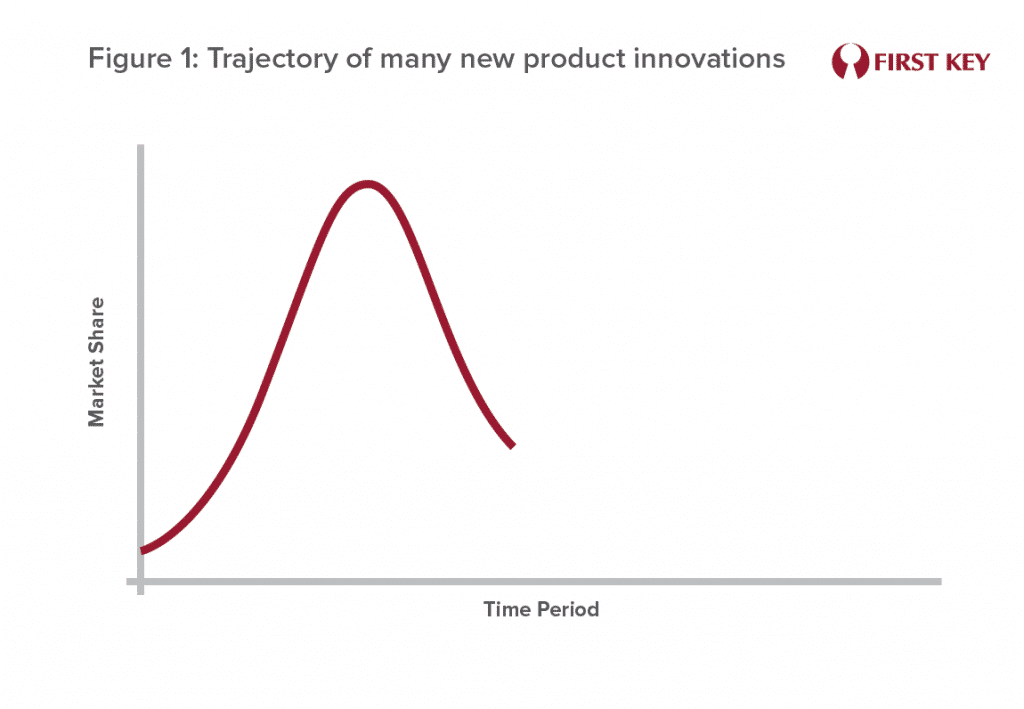

But the rise and subsequent declines of more than a few prior “fads” may have been the result of self-fulfilling prophecies on the part of the product’s management. Figure 1 shows a trajectory that has been followed by many new products after their introduction: surging short term sales, followed by a dramatic drop-off.[i] Just as the initial surge sparks additional investment by managers unwilling to miss out on a bigger-than-anticipated opportunity, the drop-off and subsequent declaration of “fad” results in a pullback of almost all investment.

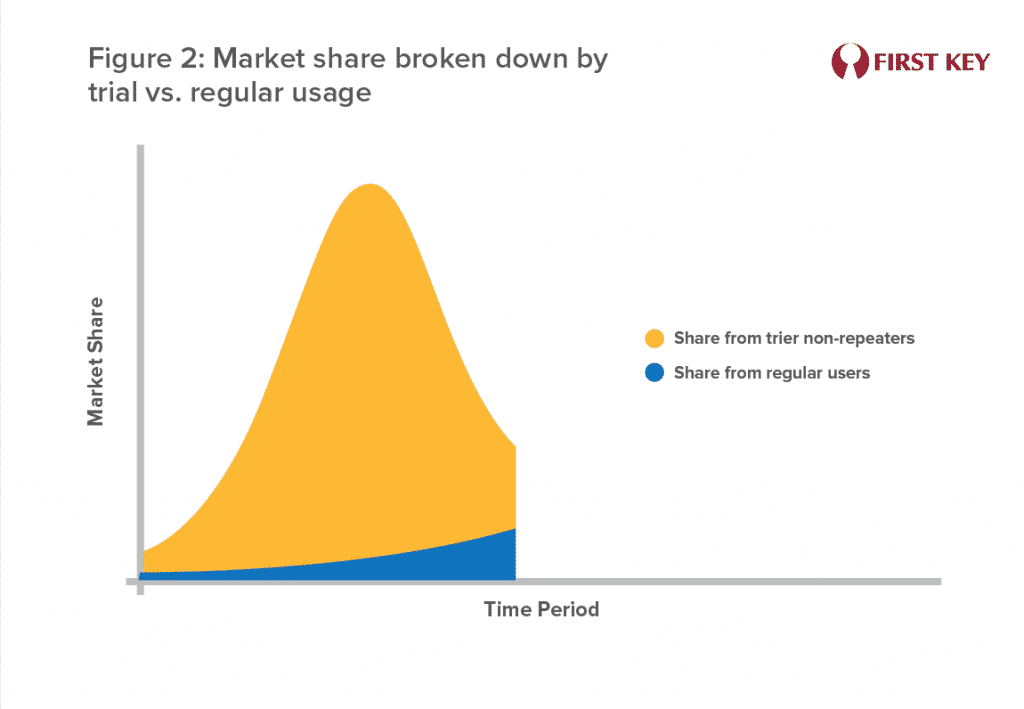

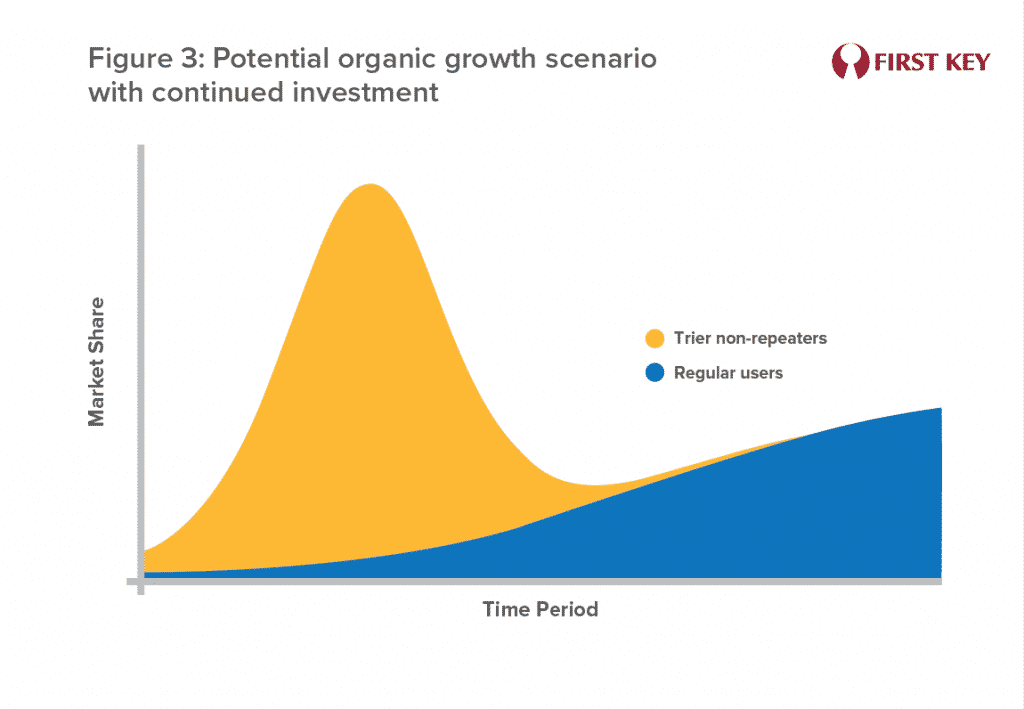

First Key has experience working on some of these and analyzing the underlying dynamics. Figure 2 shows something that many marketers forget about consumers: one person’s fad is another person’s new long-term choice. The market share over time can be broken down into what’s been sourced from trier non-repeaters (essentially the fad component) and what’s been sourced from a growing base of long-term regular users. And Figure 3 shows the natural, organic growth of both components when management recognizes that the drop-off is not indicative of the product’s long-term potential and continues to invest.

But it can be tough to justify further investment in a product that appears to be in a death spiral, and so that investment is seldom forthcoming. It’s a risk few are willing to take. But we would nonetheless argue that the continued downward trajectory of many of these past products did in fact represent self-fulfilling prophecies.

Why are big brewers recently more willing to invest and be patient with their investments than they had been in past decades? There are many reasons, including the need to look beyond beer to smaller and emerging segments as the category continues its struggles to grow. Another may well be the example set by small producers who often demonstrated patience in creating small-but-viable categories, such as craft brewers.

A significant factor may also be the evolution of new product business models, from developing everything in-house to building partnerships and equity stakes, including a markedly increased role for contract brewing.

A 1997 television ad for Miller genuine Draft proudly declared “It’s time to drink beer from vats the size of Rhode Island,” a tongue-in-cheek defense of their beer against the romance increasingly associated with small-batch craft brewers. But as big brewers attempted to compete in an increasingly fragmented market, the downside of those big vats became apparent. Making smaller and smaller batches of craft-style beer, or flavored malt beverages (FMBs), or others, in a brewing vessel designed for multi-million-barrel brands was often a logistical challenge, very time-intensive and labor-intensive.

The bottom line of all this is that, thanks to a comparatively newfound patience, we may see more new product market shares showing long-term trajectories described by Figure 3, and fewer prematurely truncated growth curves like Figure 1. But these schematic examples may encourage some who would otherwise be inclined toward impatience to analyze the spike in terms of triers and adopters and use those insights to make investment decisions. And in either case that will certainly help keep the innovation pipeline full for years to come.

[i] Note that none of the graphs for this article display actual data. They are schematic representations of patterns we have observed and analyzed for multiple new product introductions.