The explosive growth of hard seltzer may have caught North America’s brewers off-guard a few years ago, but at this point it’s probably safe to say most have adapted. And in this case, “adapting” may well mean producing and selling their own hard seltzer. There’s a lot to like about being in the hard seltzer business. The production process is straightforward, the margins are very good, and with the kind of consumer pull we’re seeing right now the marketing almost takes care of itself.

Elsewhere on our site you can read about our optimism for the category, in the form of “Hard seltzer’s untapped potential.” Yet here we’re going to raise a small question: is hard seltzer good for every brewer’s business? In many cases the answer is clearly yes; in others, the answer may not be as obvious as it seems.

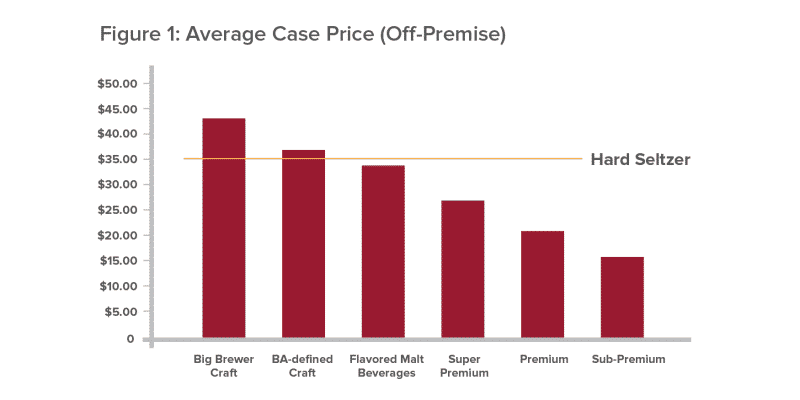

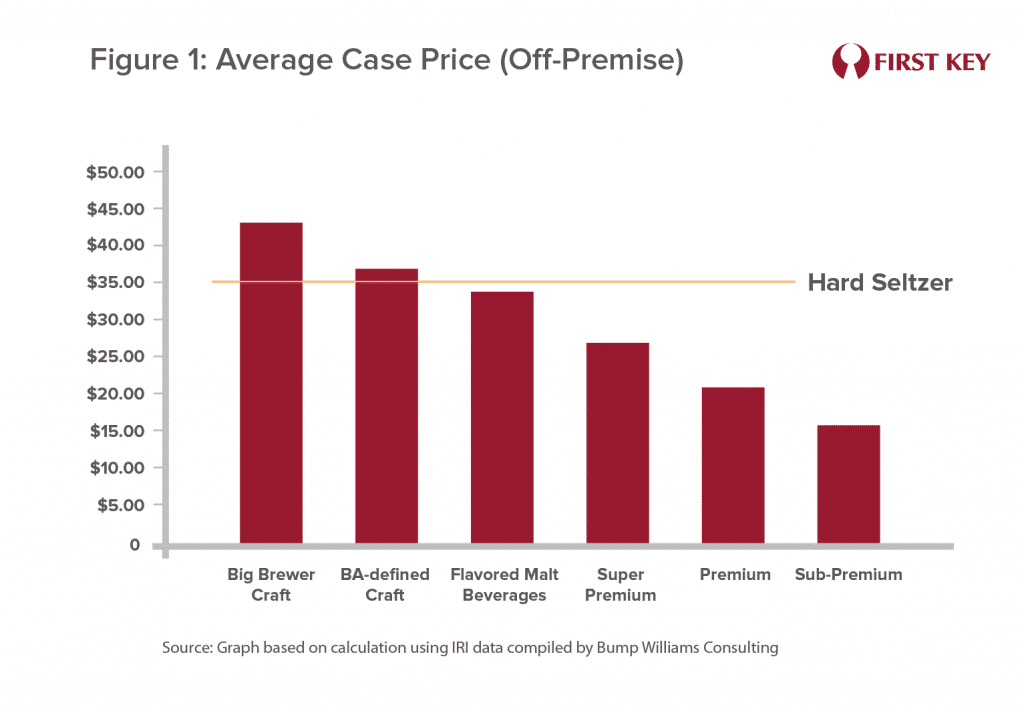

First, let’s look at the pricing. Most in the industry are pretty happy about the price commanded by hard seltzers. According to market research firm Nielsen CGA, the category was worth $2.7 billion in 2019[i]. With volume estimated at 2.8% of the beer market, that works out to $34.99 per case equivalent. Nielsen scan data for the off-premise shows White Claw fetching $33.47 a case and Truly at $31.29, all in the same ballpark.[ii]

How does that compare to beer? In 2017 the average price across the beer category worked out to $23.53, which means that on average hard seltzer represents a real trade-up opportunity.

But of course that calculation mixes apples and oranges. Figure 1 below shows that craft beer – and especially craft beer made by big brewers – commands a higher average case price than does hard seltzer. And so whether or not a given brewer’s consumers are in fact trading up when they buy its seltzer brand depends on which beers those drinking are switching away from.

Estimates of how much hard seltzer volume is coming from beer range as high as 55%,[iii] although this rate clearly varies by segment. For example, economy beer drinkers tend to be older and lower income, while hard seltzer drinkers tend to be younger and have average-to-above-average incomes. For this reason alone it seems unlikely that economy beers would be losing significant volume to hard seltzer. Premium brands may be harder hit, but again, this is a trade-up situation that, on balance, is probably a good thing for mainstream brewers.

But Nielsen’s “Beyond Beer” report, presented at last December’s Brewbound Live event, does estimate that craft beer purchasers are twice as likely as the average drinker to buy hard seltzer. Given that the pricing of hard seltzer (noted above) is fairly close to the pricing of craft brands shown in Figure 1, it may seem that a craft brewery could see its beer brands lose volume to its own hard seltzer with virtually no impact on revenues. But this in fact may or may not be the whole story, whether the brewer is large or small.

Of course there’s a valid argument to be made that adding a seltzer to the line-up is putting the cliched “saucer under the leaky cup,” that beer volume would have been lost in any case, so it may as well go to the brewery’s own seltzer brand. Whether and how to enter the category then becomes a strategic question, which requires answers to a number of initial questions:

- Do we know for certain that significant volume would be lost in any case? If so, could we replace it by introducing another beer?

- Can we charge a price point for the seltzer that matches the price point of the beer that’s expected to lose ground? Are there – or can we create – price tiers in seltzer comparable to those in craft beer? (Note that currently the only significant hard seltzer brands produced by craft breweries, Boston Beer’s Truly and CANarchy’s Wild Basin, are priced at right around $32 per case equivalent according to Nielsen – marginally less than White Claw. So as yet there is no information available on the viability of a still higher price point for hard seltzer.)

- Can a hard seltzer brand reinforce or complement our current brand equities, or would it dilute them? If the latter, is it worth investing in creating a whole new seltzer brand from scratch? In essence, are we willing to evolve from a brewery to a beverage company, and what implications does that have for all future strategies?

Getting into hard seltzer may seem like an easy decision, but the implications of these questions and their answers are all important considerations. They should be addressed before taking the plunge into a category that may influence a brewery’s brand and brand equities for a long time to come.

[i] https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2020/02/hard-seltzer-sales-in-the-us-on-trade-hit-1-2-billion/

[ii] See “Beyond Beer,” presentation at the December 2019 Brewbound Live session by Nielsen.

[iii]https://www.brewbound.com/news/nbwa-annual-convention-white-claw-maker-investing-250-million-to-increase-production-and-meet-demand