No beverage producer wants to miss out on the next big thing, which is a big part of the reason so many new products have been declared “the next big thing” – sometimes prematurely. Take non-alcohol beer. It’s almost impossible to click on a beer publication without seeing a discussion of the category’s impressive growth. For example: dollar sales of non-alcohol (NA) beer, wine, and spirits brands doubled between 2020 and 2022, with NA beer accounting for over 80% of that category.[i]) Yet that growth is coming from a very small base; NA accounts for only about 0.6% of the U.S. beer market[ii], even after all that growth on a percentage basis.

But of course, the decision to invest in development of one’s own NA beer (or wine or spirts) brand is about the future, and industry participants are speaking with their dollars when it comes to their views of that future. “We are very much in category-creation mode,” Heineken USA VP of Marketing Borja Manso Salinas told online publication Marketing Brew in justifying the company’s $50-million launch of Heineken 0.0 in the United States.[iii] And of course Keurig Dr. Pepper recently garnered headlines across the beverage industry press with their investment of $50 million for a minority stake in NA-only Athletic Brewing.[iv]

Maybe we should stop talking in terms of “the next big thing” and reframe the topic of these conversations as “the next profitable thing.” Will investments in NA beers qualify as the next profitable thing? There’s a more than reasonable expectation that the answer is “yes.” But how profitable depends at least partially on (no surprise here) Gen Z and Millennials. Younger adult drinkers often bring their leading-edge attitudes, values, and behavior along with them as they age into the majority, so let’s take a look at how these generations are interacting with low-alcohol (LA) and no-alcohol beer.

When looking for insight into those attitudes, values, and behavior there may be no better source than the Kantar MONITOR, which has been surveying Americans on these topics longer than any other source. In 2022 Kantar’s battery of questions on alcoholic beverages included “low or non-alcoholic drinks”[i] for the first time.

In terms of who drinks LA or NA beer, wine, or spirts on a regular basis, the numbers from Kantar are pretty similar to those provided by other sources we’ve seen. Three fourths of those who say they drink these beverages weekly also drink alcohol beverages weekly.

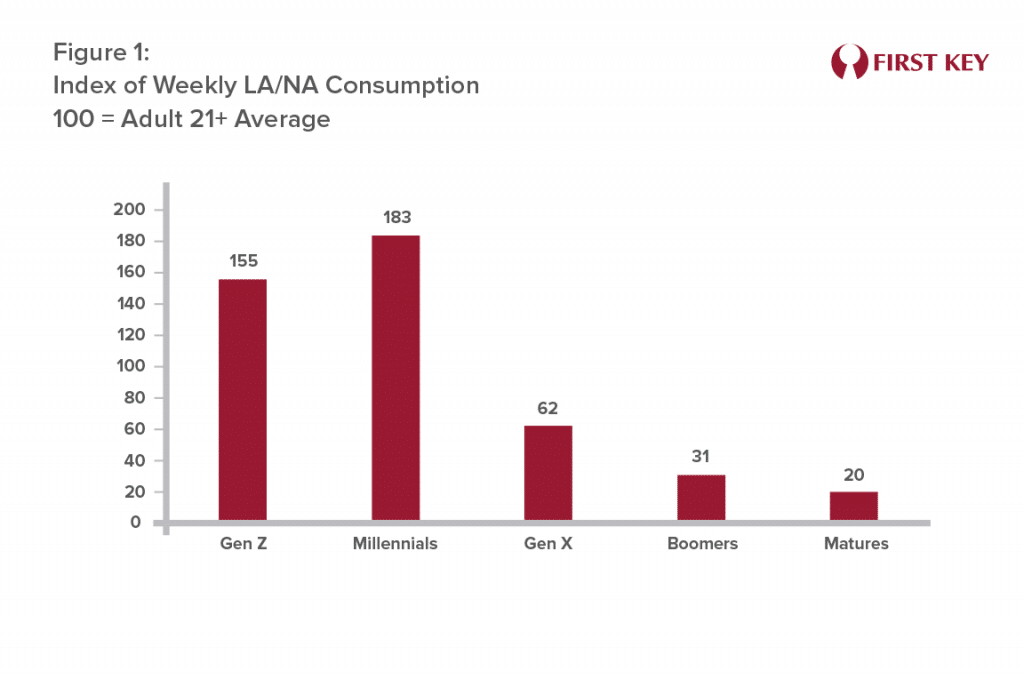

Overall, about one in eight adults report drinking an LA or NA beverage weekly. But Millennials and Gen Xers are disproportionately likely to be counted among those weekly drinkers. Figure 1 shows a consumption index for each generation, with Gen Xers 55% more likely than the average adult to drink LA/NA weekly, and Millennials 83% more likely.

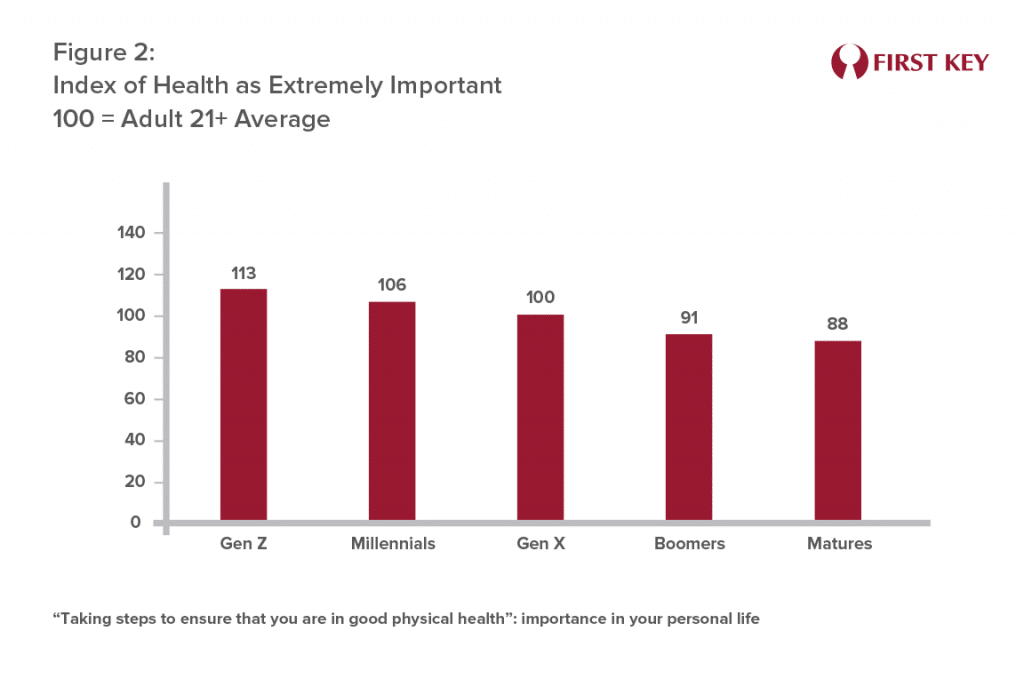

One bit of seemingly accepted wisdom is that these two younger cohorts are more health-conscious than older generations, and that this is one of their motivations for being drawn to LA/NA options. However, when asked to rate the importance of “Taking steps to ensure you’re in good physical health,” a third of adults said this was extremely important to them, with very little difference across generations. As Figure 2 shows, the index for Gen Z on this question is 113, meaning that members of this cohort are only 13% more likely than the average adult to rate health as “extremely important,” with Millennials 6% more likely. That may not be a trivial difference, but it barely supports the narrative of “young adults are more health-conscious,” if at all.

Then what are the motivations that differentiate Gen Z and Millennials that might also account for their disproportionate interest in LA/NA?

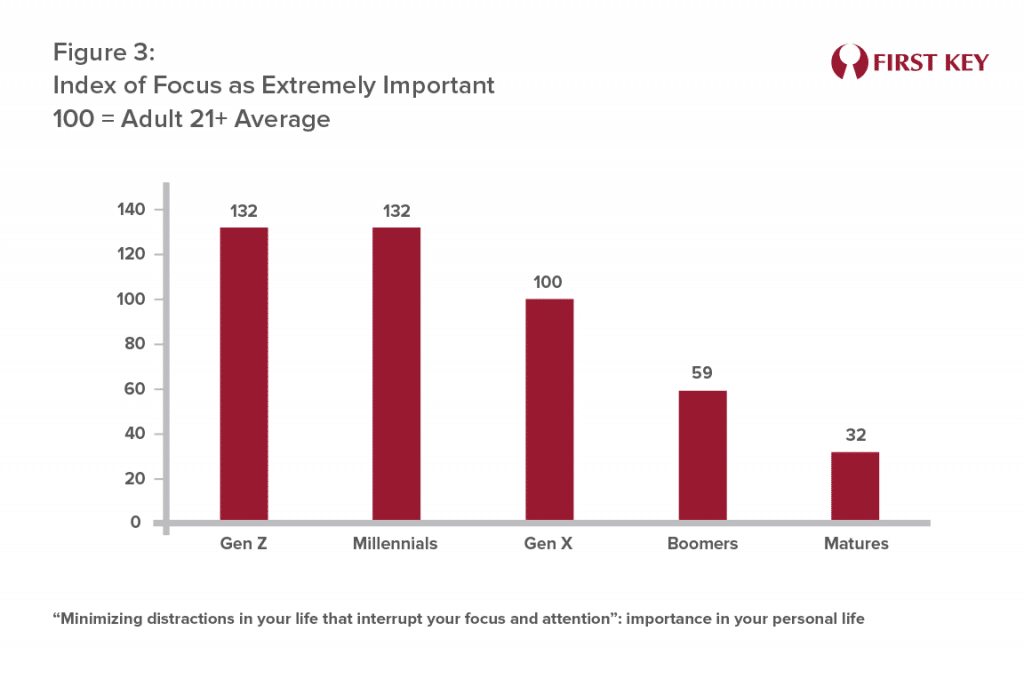

There’s evidence in the Kantar data that the answer has more to do with maintaining sobriety and focus. Overall, just over one in five adults said that “minimizing distractions that interrupt your focus and attention” is extremely important to them. But as Figure 3 shows, both Gen Z and Millennials are 32% more likely to agree with this statement. The generational skew is in fact similar to that of LA/NA beverage use in Figure 1.

We would point out that a need for focus is likely to be more occasion-specific, whereas health is likely to be more of a long-term consideration. This may offer an explanation for the considerable overlap between drinkers of LA/NA versions of alcohol beverages and the alcohol-containing counterparts. A person with a long-term health focus might arguably be less likely to be a regular drinker of alcohol beverages, period. However, someone concerned about sobriety and focus in an individual occasion may be less concerned about those motivations in a different occasion, and happy to drink beer in the latter occasion. This also has implications for positioning and marketing of LA/NA brands.

In the 1990s, Bob Weinberg, a then-prominent beer industry economist and consultant, described the price of a non-alcohol beer as “barstool rental.” He was being deliberately glib, but there’s actually some real insight there.

To thoroughly answer the question of why people drink an NA beer, we have to answer a different question: why do people drink beer? Weinberg understood that there was much about the beer experience that had less to do with the alcohol directly than the sense of community fostered by drinking beer together. Having a soft drink in hand isn’t nearly as effective in reinforcing that feeling of bonding, camaraderie, connection, whatever one wants to call it. The person drinking an NA beer still wants to fit in as much as possible.

Boisson, an emerging chain of shops selling only NA versions of beer, wine, and spirits, recognizes this potential conflict when it declares itself a “judgment-free zone.” In a Washington Post interview, CEO Nick Bodkins offered some additional perspective when he said “We’re focused on the experience. Drinking is a social construct. There’s a drinking moment. We want to help people meet that moment.”[i]

Strong brands often focus on the experience. It may well be true that the primary benefit sought by NA drinkers isn’t sobriety, but rather community. Maintaining sobriety by buying an NA beer likely functions more as elimination of a barrier to the beer experience – a means to an end, or the price of renting a barstool for the evening.

The brands that internalize that sort of message may well find NA beer to be the next profitable thing.

By Mike Kallenberger, Senior Advisor, Marketing Insights and Strategy at First Key

[i] https://www.brewbound.com/news/nielseniq-non-alc-beer-wine-and-spirits-doubled-since-2019-beer-accounts-for-85-3-of-non-alc-category

[ii] https://www.sightlines.news/analysis/non-alc-beer-sales-grow-faster-than-geographic-hot-spots

[iii] https://www.marketingbrew.com/stories/2021/09/27/brands-are-figuring-out-how-to-sell-non-alcoholic-beer-in-a-growing-market

[iv] https://craftbusinessdaily.com/the-dr-is-in-on-athletic-with-kdps-50-million-investment/

[v] As in the case of most surveys, what “low alcohol” means here is whatever it means to the individual respondent, so we can’t say for certain what the criterion might be

[vi] https://www.washingtonpost.com/magazine/2022/07/25/cocktails-sober-curious-drinking-alcohol/