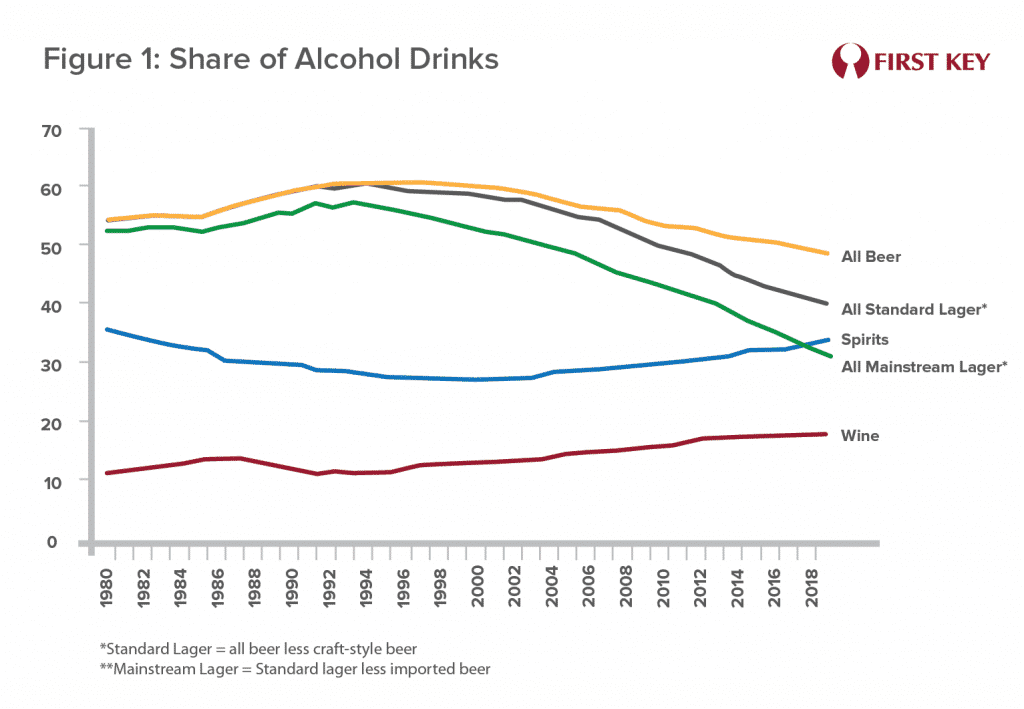

In the United States beer’s share of all alcohol drinks peaked at 61% in 1993 and has been declining ever since. Meanwhile spirits and wine have split the spoils almost equally, with gains of 7 and 6 percentage points, respectively. Spirits now account for 34% of all drinks consumed by Americans.

By itself this is not news to almost anyone in the industry. But here’s what few have noted: If we subtract imports and craft-style beer in order to focus on mainstream lager, an unprecedented transition occurred in 2018: spirits passed mainstream lager to become the market share leader in terms of drinks consumed. (See Figure 1.)[i]

It’s no wonder America’s biggest brewers are branching out into other beverages. Any marketer who’s ever confronted the impact of changing consumer tastes has at one time or another come across Charles Darwin’s quote, transplanted from an evolutionary to a business context: “It is not the most intellectual or the strongest of species that survives; but…the one that is able to adapt to…the changing environment in which it finds itself.”

But adaptation is more than chasing the latest trend. Simply introducing new products in adjacent growing categories can often be a reliable approach to replacing lost volume – the “saucer under the leaky cup,” as one marketing cliché puts it. But what would it take to solve the bigger problem – namely, fixing the crack in the cup?

“People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole.” This insight is frequently attributed to former Harvard professor Theodore Levitt. In his classic Harvard Business Review article “Marketing Myopia” Levitt encouraged companies to ask themselves “What business are we in?” The answer, he assured them, was not about selling products but rather meeting customers’ needs.[ii]

But the context for defining those needs matters as well. In a 2019 article on the HBR website authors Omar Abbosh, Vedrana Savich, and Michael Moore discussed their study of 840 companies and the relative success of each one’s innovation efforts. “Only 31 of those companies that had increased their spending on innovation by more than 50% between 2012 and 2017 also self-reported being ‘very satisfied’ with the business benefits.”[iii]

What did those 31 do differently? Two practices stood out, the first involving technological innovation. But as Levitt pointed out “When R&D produces breakthrough products, we may be tempted to organize our companies around the technology rather than the consumer. Instead, we should remain focused on satisfying customer needs.”

The second stand-out practice found by Abbosh, Savich, and Moore builds on Levitt’s premise. The 31 successful companies “deliberately target[ed] consumers’ ‘higher needs’ – such as autonomy, happiness, and social connections — at a higher rate.”

Looking at the thirty years of mainstream lager’s decline, we see that share being taken first by imported beers, then spirits, then craft beer – and now hard seltzer. (We’ll ignore wine’s growing share for the sake of simplicity.) The bigger brewers responded to each of these threats in turn, first by importing their own international brands, then by introducing spirits-branded FMBs, then by buying craft brewers.

But what if we had asked what higher level needs each of those successful drinks had been targeting?

On the surface imports were often about status, although Corona overtook Heineken in part because they sold more than status – they sold tranquility, at an almost existential level.

Different spirits brands of course sold different benefits, but by the early 2000s many of the strongest brands were selling heroism – think of the protagonists of “To Life, Love, and Loot” (Captain Morgan) or “Live with Chivalry” (Chivas Regal). (And when a beer brand – Dos Equis – did start selling heroism, it was pretty successful.)

And the higher level benefit sold by many of the emergent craft beer brands in the 21st century was a sort of rebellious creativity.

It may or may not be too early to clearly state what hard seltzer is selling, but that may be the question most worth asking in the beer industry today. The health and wellness trend has been cited by many, but this need is still more tangible and doesn’t register by itself at the highest, emotional level. Could a beer brand steal some of the limelight back by finding an even better way to sell what hard seltzer is selling, at least in the eyes of some drinkers?

“Our business is not just making beer. Making friends is our business.” It’s part of Anheuser-Busch lore that Adolphus Busch once explained this to Ernst Anheuser. It may be no coincidence that the brewery that made this their mantra went on to become the largest in the world.

Today, with beer-drinking occasions experiencing unprecedented disruption due to the coronavirus situation, the average beer drinker may see “higher needs” as the least of their worries. But in this seemingly unstable new world we’re also seeing unprecedented adaptability, from relaxed restrictions on home delivery of beer to beer drinkers arranging “virtual happy hours” with friends. Some fundamentals never change. (After all, that’s why we call them “fundamentals.”)

In spite of headwinds, long-term and short, beer is not past its prime. The validation for that prediction may be found in a better approach to defining the business we’re in.

[i] Data from the Beer Institute, DISCUS, and The Wine Institute; drinks are defined using the convention of 1 beer = 12 ounces, 1 spirits drink = 1.5 ounces, and 1 glass of wine = 5 ounces

[ii] Levitt, T. (1960). “Marketing Myopia”. Harvard Business Review

[iii] https://hbr.org/2019/03/what-sets-the-most-effective-innovators-apart