For an industry hungering for positive news about Gen Z’s impact on the future of the alcohol beverage market, that’s exactly what a recent Rabobank report provided. In “The real reasons Generation Z is drinking less alcohol,” veteran beverage analyst Bourcard Nesin took a fresh approach to analyzing the sometimes opaque-seeming motivations of this cohort. His main finding: “Gen Zers’ alcohol consumption will likely increase significantly as they age, such that by their mid-30s, their consumption will be much closer to that of previous generations.”[i]

Positive news, indeed, and good news spreads quickly. Within days, understandably, the report’s insights were touted in virtually every major beer industry publication. Thus, rather than summarize and rehash the analysis – all of which was insightful (though we found some aspects more compelling than others) – we’ve decided to share some perspectives on a related, but narrower question: When Gen Z does drink alcohol, what are the reasons it chooses beer less often?

There are multiple potential explanations that could and should be explored, but for purposes of this article we’ll address one particular hypothesis: Beer is an acquired taste, and Gen Z has had less motivation to acquire that taste.

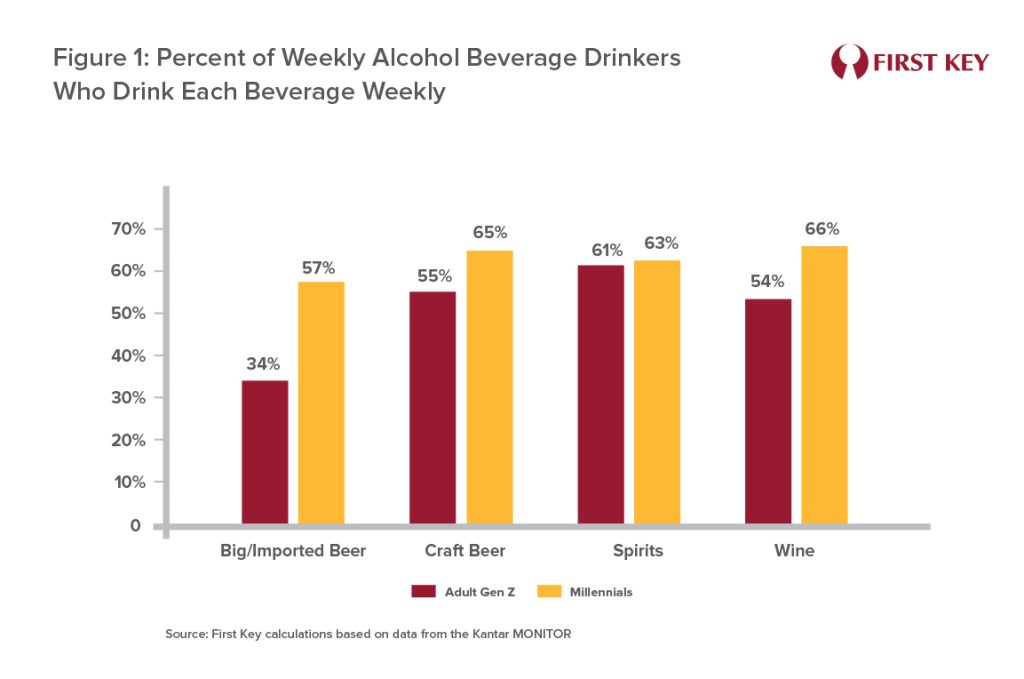

Data from Kantar’s MONITOR confirms that Gen Z alcohol beverage drinkers are less likely to choose beer than are Millennial drinkers. The base for the calculations graphed in Figure 1 is restricted to those who drink any alcohol beverage at least once a week. Note that spirits are chosen as frequently among Gen Z drinkers as among Millennial drinkers, but the former cohort drinks both beer and wine less frequently than do their older counterparts. There’s a particularly sharp drop-off in frequency for “big/imported beer,” but craft beer is also chosen significantly less frequently among Gen Z drinkers.

In his keynote talk at the 2025 Craft Brewers Conference, Brewers Association CEO Bart Watson presented survey data addressing the reasons people don’t drink craft beer more often. The number one response by far: “I don’t like the flavor,” a sentiment expressed by just about half of the survey sample.

Clearly, there have always been and always will be people who don’t like the taste of beer. This statistic alone, while useful, doesn’t tell us whether there are more beer-flavor-rejectors today than there were a generation ago. But let’s assume for the moment that Gen Z is less likely to drink beer because they’re more likely to dislike the flavor. How might that state of affairs have come about?

It’s probably not controversial to say that beer is an acquired taste for many people, if not most people. Think about the reaction of someone tasting beer for the first time – maybe it’s your younger self, maybe it’s a wholly imaginary beer novice. Odds are that your, um, we mean their reaction was less than positive, maybe even an outright grimace and an “Eeew!” Scientists tell us that this sort of reaction to bitter flavors in general is basically programmed into our genes because, back in the prehistoric era when nature was busy screening human beings for pro-survival traits, plants with bitter flavors (like hops) were more likely to be poisonous (fortunately, unlike hops). And so those who determined that their first taste of something bitter would be their last were less likely to die from poisoning and more likely to be around long enough to pass on their genes.[ii]

However, returning to the present era, even though our imaginary beer novice failed to appreciate the joy of hops on their first taste, they did in fact press on to take a second, third, and fourth taste, and ultimately many more. Why?

If they’re like most people, their first taste of beer was at an age when they were young and impressionable, and in a social setting besides. In all likelihood, they wanted to fit in with the people around them, and the people around them were drinking beer.

While there are a lot of behaviors in a social situation that a newcomer might feel compelled to emulate, drinking beer may well be near the top of that list. Why? Because drinking beer is an inherently social activity. It’s even commonplace for the group to drink beer from a communal source – a keg at a party, or at least a pitcher at a table in a bar. Drinkers are often literally gathered around the beer in an approximation of a circle. But even when bottles or cans are the vessels of choice, choosing an altogether different beverage can feel awkward if not outright alienating to a novice drinker, and relatively few are willing to do so.

And so, despite their initial negative reaction, many people will drink beer again and again for social reasons – and discover that they’re starting to actually like the taste. In effect, they are (inadvertently?) conditioning their palate to like beer. It’s actually not uncommon for sufficient repetition of a stimulus – not just a flavor, but a piece of music, a human face, almost anything – to evolve a given individual’s response from “dislike” to “like,” a phenomenon psychologists call the mere exposure effect.[iii]

But if beer is in fact an acquired taste motivated by social interaction, over the past two decades there have been fewer and fewer opportunities for that beneficial exposure to beer to take place, as Americans have been spending less and less time with friends.

Much has been written about the 21st century social environment and the declining amount of time North Americans spend with friends. Political scientist Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone brought the issue to a wide audience in 2000[iv], documenting an erosion of America’s social bonds over the last quarter of the 20th century. More recent statistics show that this trend has continued, as time spent with friends has only further eroded, particularly among young adults. The Rabobank report discusses this as well: “As their lives move online, young people have fewer in-person social interactions. Since the vast majority of drinking occasions for young people are social ones, fewer hangouts and fewer parties mean less drinking.”[v]

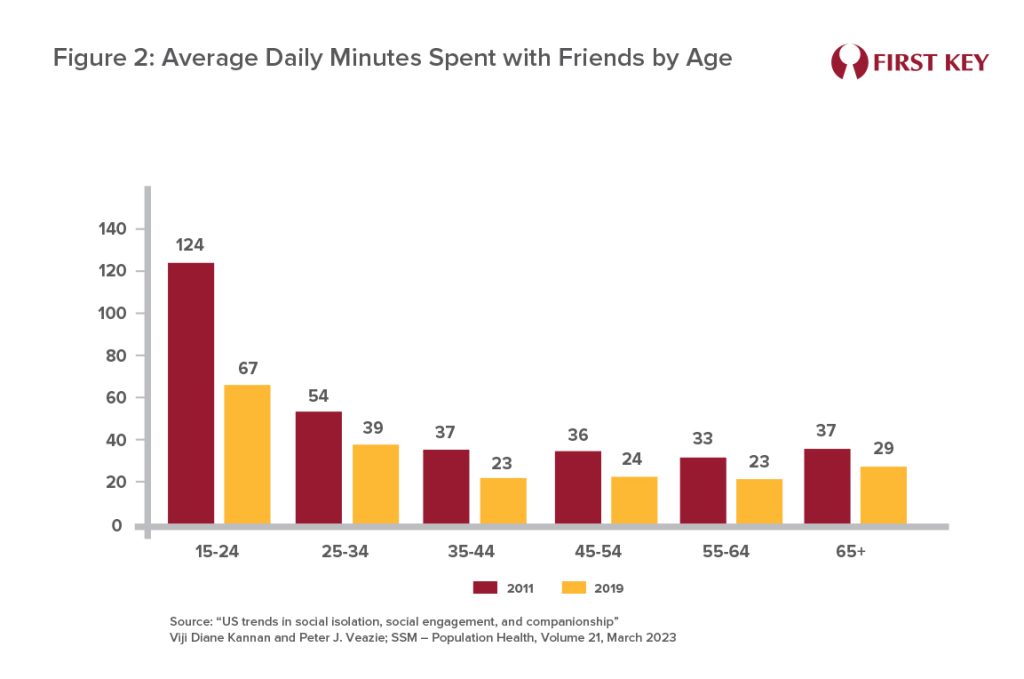

A 2023 study analyzed data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey, illustrating just how extreme the changes have been for young adults.[vi] The survey uses a diary approach to find out how many minutes participants spend in various activities, including “social engagement with friends.”

Figure 2 compares the amount of time people of various ages spent with friends in 2011 and 2019. (In the absence of data broken out for 21-24-year-olds, we used 15-24 data as a surrogate for young adults.) The numbers were down for all ages, but none more so than for 15-24-year-olds, whose time with friends was almost cut in half, from just over two hours to just over one hour a day. For all other ages, the decline was around 10-15 minutes a day. (Data from Statistics Canada[vii] describe similar trends.)

Here it’s worth noting that the 15-24-year-olds surveyed in 2011 were Millennials, while the 15-24-year-olds of 2019 were Gen Z – meaning that the “fewer hangouts and fewer parties” cited by Nesin in the Rabobank report are indeed characteristic of the latter cohort. And that may also mean a typical 20-something Gen Z has had fewer opportunities to drink beer and acquire a taste for it than did a typical 20-something Millennial.

But does less-frequent consumption in one’s early days as a drinker really result in a lifelong dislike for beer? Wouldn’t our novice drinker acquire a taste for beer eventually?

That may happen, but not necessarily. Scientists tell us that it can take up to 20 experiences with a once-disliked stimulus before the mere exposure effect kicks in and liking starts to develop.[viii] But drinking is such an infrequent activity for many Gen Zers that it may take a year or longer for some of them to accumulate 20 beer-drinking occasions.

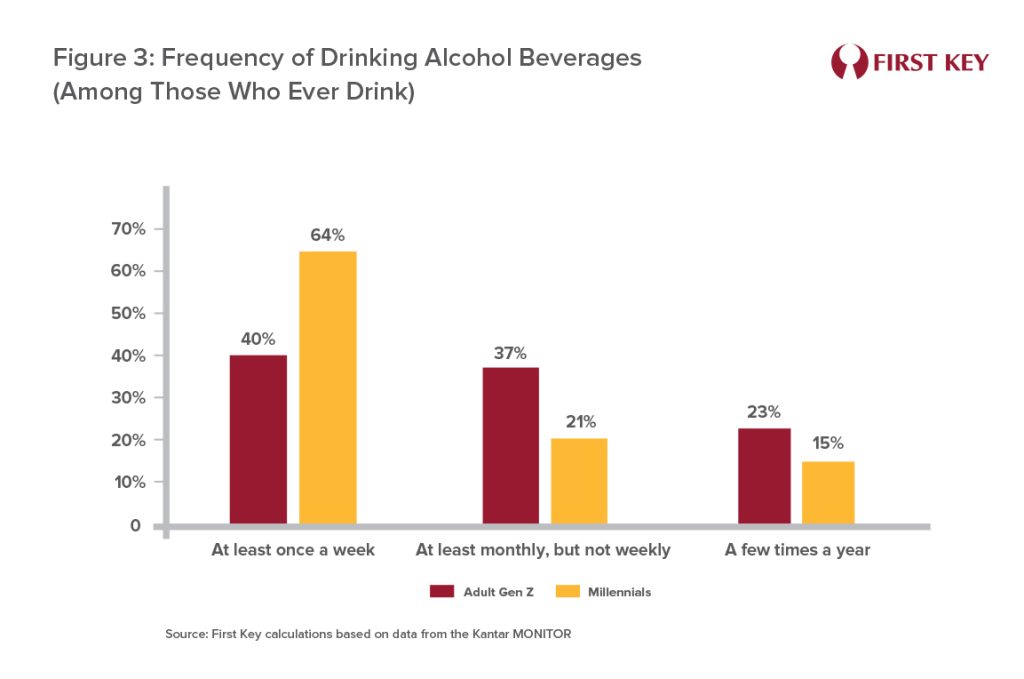

For additional perspective on this question, we turn again to the Kantar MONITOR data. Figure 3 compares Gen Z and Millennial drinkers in terms of how often each consumes alcohol beverages. While almost two-thirds of Millennial drinkers imbibe at least once a week, only four in ten Gen Z drinkers do. Meanwhile, over a third of Gen Z drinkers imbibe a few times a month but not weekly, and almost a quarter drink only a few times a year.

It’s time for some guesstimates and back-of-the-envelope math. “At least monthly, but not weekly” could mean anywhere from 1-3 occasions per month. Let’s say the average for this group is around twice a month. That means it would take almost a year for someone in this group to accumulate 20 beer-drinking experiences, assuming that they drink beer on every alcohol beverage occasion. “A few times a year” encompasses no more than 11 occasions and as few as 3. For the people in this group, it would require anywhere from two to ten years to experience 20 beer-drinking occasions – and keep in mind that based on their reported behavior almost a quarter of Gen Z alcohol beverage drinkers belong to this group.

One tentative conclusion based upon all this might be that the propensity for Gen Zers to choose beer may well increase over time, as the process of acquiring the taste is simply slower, but also that the ceiling on the ultimate number of Gen Z beer drinkers may be lower relative to previous generations.

From the perspective of their own businesses, many brewers are doing exactly what they should be doing to address this: participating in one way or another in the categories that are not only growing, but compatible with their own production capabilities. These may include RTD canned cocktails, hard seltzers, and even hard juice or soda. Flavored beer can also fit in this group.

Each of these categories has one clear advantage over traditional beer: they don’t present the same hurdles in terms of acquiring the taste, as they offer some very familiar flavors to novice drinkers. Here it’s worth pointing out, as Figure 1 shows, spirits are the one alcohol beverage category that’s as likely to be chosen by Gen Z drinkers as Millennials drinkers. A reasonable explanation for this is that spirits are typically mixed with sodas, juices, and energy drinks that are already familiar to the novice palate – meaning that they’re effectively the same as RTDs.

But from the perspective of our reluctant beer novice, these categories also have an advantage over spirits as an alternative to beer since drinking any one of these beverages from a can, unlike a mixed drink in a cup or glass, is less likely to make him or her stand out from the group in a room full of peers drinking beer from a can.

Broadening a brewery’s beverage portfolio for the sake of incremental sales can be important. Yet for many in the business, this step may be oddly unsatisfying and ultimately an incomplete solution, for the simple reason that sharing their love of beer is part of what motivates them.

When many drinkers say “I don’t like beer,” what they may mean is “I don’t like IPAs.” There are, in fact, more than a few drinkers whose knowledge of beer barely extends beyond IPAs.[ix] And of course, to the extent that bitterness is probably the key attribute that makes beer a somewhat difficult-to-acquire taste, bitterness is probably more associated with IPAs than any other style. While these IPA-focused non-beer drinkers may well be aware that other styles exist, those other styles are tangential to IPAs on their mental radar.

In a recent interview for the Brewbound podcast, Bart Watson touched on this topic, citing the early days of craft when education was such an important part of the category’s development.

“Brewers know how to do this. It’s maybe a muscle we need to re-flex, to put more emphasis on. It doesn’t mean we need to go away from IPA, [we need to say] ‘Hey, we’re IPA and this,’ show people there’s a place for them. We can increasingly do that with other beverages and beer. We don’t need to say you have to go to a seltzer, or you need to go to an RTD cocktail, we have beer options you should try along with those.” [x]

By itself, education certainly won’t be a magic pill that provokes reconsideration on the part of every drinker who’s on the fence about beer. But at minimum it just might enable more brewers to celebrate beer in an inviting way – a value that has been central to craft beer culture since the beginning. And then, if Nesin is right and Gen Zers really do increase their consumption of alcohol in the future, they just may choose beer more often as well.

[i] https://media.rabobank.com/m/18086d3a9adee411/original/The-real-reasons-Generation-Z-is-drinking-less-alcohol.pdf

[ii] Here we’re paraphrasing various sources, although a good summary of these arguments can be found in https://www.craftbeer.com/craft-beer-muses/genetically-programed-hate-hoppy-beer

[iii] https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1968-12019-001

[v] https://media.rabobank.com/m/18086d3a9adee411/original/The-real-reasons-Generation-Z-is-drinking-less-alcohol.pdf

[vi] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235282732200310X

[vii] https://www.statcan.gc.ca/

[viii] https://www.craftbeer.com/craft-beer-muses/genetically-programed-hate-hoppy-beer

[ix] See “A New Breed of IPA Drinker,” The New Brewer, September-October 2018

[x] https://www.brewbound.com/news/brewbound-podcast-brewers-association-ceo-bart-watson-on-the-state-of-the-craft-beer-cbc-vibes-gabf-changes-and-flavor-trends/