References to “category blurring” are everywhere in the alcohol beverage industry lately. A Nielsen IQ Analysis published on June 25, 2020 offers us insights into “a blending and blurring of options, brands, and categories.” In a July 9, 2021 piece for Good Beer Hunting, Kate Bernot tells us that “the lines between traditional categories in alcohol have become blurred to an unprecedented degree.” And on October 18 of 2021, Beer Business Daily reports on “the growing ranks of line-blurring brands.”

But blurring in the world of alcohol beverages isn’t confined to product categories. A recent edition of Beer Business Daily commented “…while there is ‘blurring’ in production, the real action is happening in distribution…”

And then there are reports that dayparts are also blurring, thanks in part to drinkers’ adaptations in response to pandemic-driven lockdowns and bar closures in 2020. “We don’t have that traditional lunch anymore, but we have an extended lunch,” reported John Lane of Ohio’s Winking Lizard on-premise chain. In an interview with Beer Business Daily he discussed “…people coming in at 2 or 3 in the afternoon, hanging out; we’re getting an early happy hour…it kind just flows through.”

If we can no longer tell the difference between late lunch and early happy hour, then there’s no such thing as lunch or happy hour.

In fact, the blurring of previously-recognized boundaries in marketing has been going on for well over a decade. This hasn’t been discussed nearly as much as it could have been or should have been – not because it’s not significant, but arguably because it’s so significant that it may signify the functional end of a tool marketers have embraced for generations, namely market segmentation.

Sure, the real world has always been a little blurry. Segmentation frameworks have essentially “assumed away” that blurring in favor of theoretically neat boundaries between segments, and that approach has been more than workable historically. However, a situation in which blurring becomes the norm is anathema to the whole concept of segmentation.

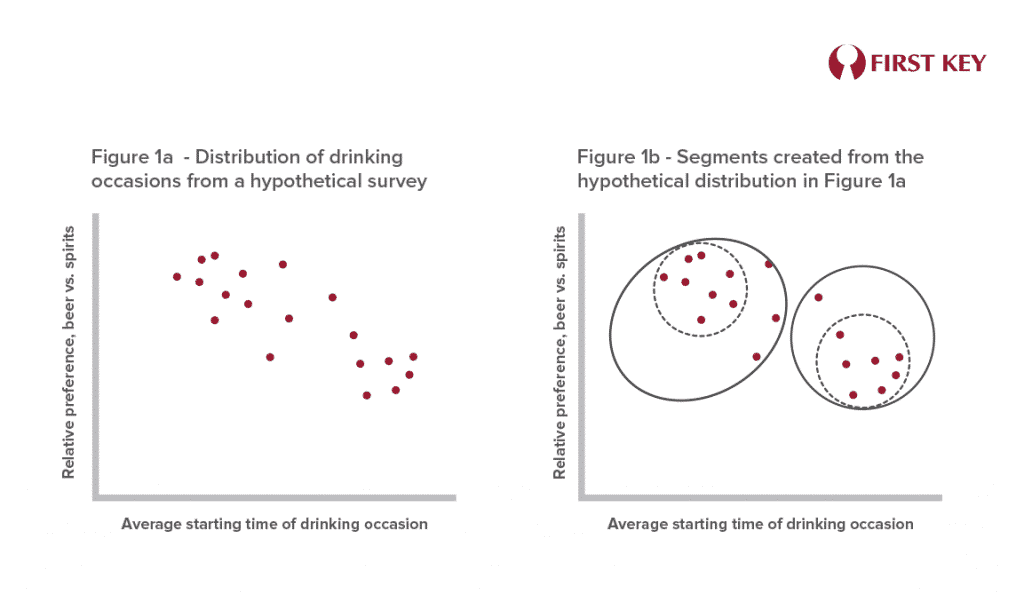

Let’s do a quick refresher on what segmentation means to a market researcher. For this example, let’s say we’ve done a survey, and among the things we asked respondents about were the starting time of their most recent drinking occasion and their relative preference for beer versus cocktails in that occasion. We can graph the results of these questions as we did in Figure 1a, where each data point represents one observation of a respondent-occasion.

By definition, members of a given segment are similar to each other but different from members of other segments. So, eyeballing Figure 1a, some of the data points do cluster together more so than others. In Figure 1b, circles with a dashed circumferences have been drawn around two collections of observations. This is essentially the “first pass” at dividing the set of observations into two distinct segments. Segment 1 consists of occasions with earlier starting times and a greater relative preference for beer. Segment 2, then, involves later starting times and a relative preference for spirits. But four observations are in a sort of void in between; they could arguably belong to either segment. We can (and typically do) assign each to a segment based on pure math, i.e., which of the two dashed circles it happens to be closest to. So each of the two circles in Figure 1b has been expanded to include the four in-between observations in one segment or the other.

Our segmentation scheme is now essentially complete. We accept a trade-off – in order to make the segmentation simple and easy to work with, we ignore the fact that some individual data points have been assigned to a segment somewhat arbitrarily. The simplistic nature of this example aside, that’s essentially what statisticians armed with sophisticated segmentation algorithms are trying to do. And, as mentioned, this pragmatic approach to the in-betweeners works very well.

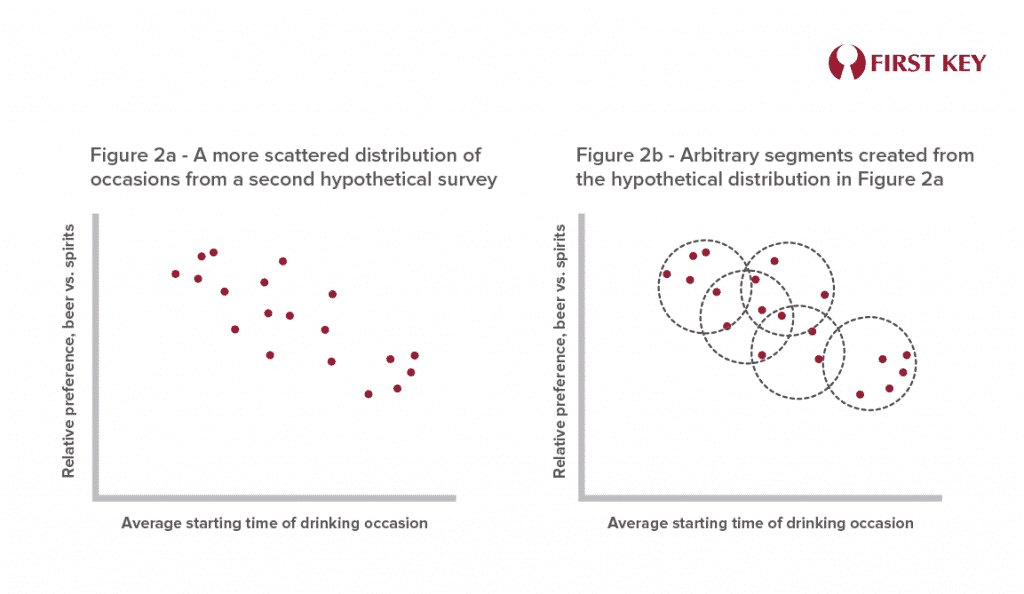

But now look at Figure 2a. It replicates Figure 1a, but five of the data points have moved, albeit only slightly. (You can play a variation on “Where’s Waldo” by trying to identify which points have moved, but it doesn’t really matter for our example.) This is the blurring we’ve been talking about, in schematic form. The starting times of the occasions are spread across all hours, and the drink preferences spread out along with these. Unlike Figure 1a, in which just a very few observations straddle the divide between the two theoretical segments, one might be hard-pressed to eyeball this graph and see any segments at all – just a spectrum of observations. Figure 2b includes a slew of circles placed almost arbitrarily on the graph, none of which has any greater claim to representing a true segment than any other.

In Figures 1a and 1b, by taking the observations that blur the two segments and arbitrarily assigning them to one or the other, no real harm is being done. There’s always “noise” in any model, and those observations essentially represent noise. But now it’s not just a few assignments of observations that are arbitrary; it’s the entire segmentation scheme.

What does this imply for marketing in the alcohol beverage category? Marketing programs are typically designed for different segments, in this case different dayparts. The communication of benefits in any marketing program is tightly focused on different consumer needs in different segments. For example, in happy hour the message might be about relaxation and reward for a hard day’s work. At mealtime it might be about simple enjoyment, of food or the conversation. As segments such as dayparts lose their individual relevance, two related sets of implications may result.

First, in an effort to develop communication that’s widely appealing throughout the blurred occasion, marketers may be forced to develop communication that’s less focused and therefore less compelling. But it’s just as likely that a smart, adaptable marketer may well identify a new consumer need and an associated benefit that’s widely relevant in this new occasion and communicable with great clarity.

But if we ultimately reach the point where blurring is the norm across occasions, across need-states, across beverages, and across consumers, the segmentation specialists may have to adapt as well, because their old line of work may never be the same.