It wasn’t necessarily an easy journey, but production of an iconic Pittsburgh brand has returned home.

No, the city that once produced 60% of America’s steel won’t be seeing steel production returning to the city any time soon (although Pittsburgh’s economy has adapted quite nicely in any case), yet Pittsburgh will always be the iron city. An iconic identity doesn’t fade quite so easily, nor does the pride in the heritage built on that historical identity. And so, fittingly, the beers of Pittsburgh Brewing Company, which has experienced its own ups and downs over the decades and ultimately moved its production out of Pittsburgh in 2009, are now being brewed in the company’s namesake city once again, thanks to one man’s vision and the hard work of a lot of people.

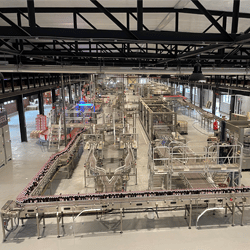

An impressive new brewery has taken form in the former PPG glass factory on the banks of the Allegheny River. With a capacity of 200,000 barrels at peak efficiency, the facility is well-prepared to support further growth in the already brisk sales of the company’s flagship Iron City and IC Light beers, and more.

Two years ago this situation may have seemed improbable, but not when one recognizes the story’s themes of pride, want, and will – a mantra that those involved often use to describe how it all unfolded. It had a lot to do with the vision and persistence – not to mention the willingness to invest in an iconic brand in need of reinvigoration – – of a man named Cliff Forrest, along with the can-do mindset of his extended team.

The newly refurbished building is “quite remarkable,” according to Mike Gerhart, Senior Advisor, Technical Services at First Key Consulting. “It mixes new-age stainless steel with this kind of late industrial brick and iron.” It sits on a 42-acre site with 170,000 square feet under-roof, plenty of greenspace, and beautiful river frontage that has spawned plans for a future marina.

While the building itself is a tangible embodiment of Pittsburgh Brewing’s transformation, few people are in a better position to describe the change in the company’s intangibles than its president, Todd Zwicker. This is Zwicker’s second stint with Pittsburgh Brewing, after experiencing the company’s troubled history in the 1990s and 2000s first-hand.

“Not a lot of great things happened here [in the 1990s],” he said. “The previous six ownership groups ended up with financial problems. Obviously, people got into it for the wrong reason… None of them put a nickel into the place. They wanted to extract out as much as they could, and obviously there’s nothing to extract out when there’s only bones left. They all found that out the hard way.”

Things began to change when Forrest, who grew up in Pittsburgh and went on to found Rosebud Mining, took an interest in the brewery and eventually bought it from Verus Investment Partners, closing on the sale in 2018. “He loves Pittsburgh Brewing and his goal was to bring the brewing back to Pittsburgh and put the company back on the map,” Zwicker explained. “There’s nobody else in the world who would do what he’s doing. It’s not a money grab by any stretch. It’s the pride, the want, and the will to rebuild what was once a proud brewery.”

Most companies, inside or outside the brewing industry, experience ups and downs over the course of generations. Since its founding, Pittsburgh Brewing may have experienced more of those changes in fortunes than most.

The company traces its roots to 1861, when a German immigrant named Edward Frauenheim founded the Iron City Brewery and soon built it into what was reportedly America’s largest outside the East Coast. Fueled by its early success, the company moved its operations into a new building in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood, which still houses its offices today. When consolidation became popular in the American business community in the 1890s, Iron City joined 20 other Western Pennsylvania breweries in a merger that created the newly christened Pittsburgh Brewing Company. At the time it was the nation’s third largest.

In the half-century after America’s emergence from Prohibition in 1933, Pittsburgh Brewing remained one of America’s dwindling number of regional and local breweries, as one after another fell to forces of industry consolidation. Though the company remained open and independent, sales were shrinking while the country’s largest brewers became larger.

But the company experienced a renaissance of sorts under the leadership of Bill Smith, who took over as president in 1978. Smith, who became a somewhat legendary figure within the beer industry, presided over the introduction of IC Light beer. The brand quickly established itself as Western Pennsylvania’s favorite light beer, with a market share of over 75%. Before long, Pittsburgh Brewing’s sales doubled with production rising above a million barrels in the early 80s.

Smith’s success resulted in him being hired as president of the much larger Pabst Brewing in 1980. Though he began the process of merging Pabst with his former employer, that deal fell apart as Pabst faced its own challenges, and Pittsburgh Brewing found itself limping into the 1990s with limited resources to challenge the growing dominance of the big brewers. The brewery changed hands multiple times, passing through the control of that series of failed ownership groups. By that time, “People were drinking IC Light, but it was a push,” Zwicker said. “Iron City, one of our core brands, was struggling mightily.”

In 2009, the city and its beer drinkers faced another blow to their collective pride: the brewery made the decision to stop brewing Pittsburgh Brewing beers in their namesake city, instead attempting to conserve their dwindling resources by having the brands contract-brewed at the former Rolling Rock brewery in Latrobe, Pennsylvania.

Once Forrest bought the brewery, there was – finally – new energy in the air. Returning the brewing to Pittsburgh was a priority, but it was quickly established that renovating the Lawrenceville brewery would be complex and cost-prohibitive. Attention then turned to the former PPG facility that Forrest had bought following his purchase of the brewery. But while that redevelopment turned out to make more economic sense, it was not necessarily a simple task in its own right.

“Obviously nobody down here at Pittsburgh Brewing had built a brewery,” Zwicker said. “Hiring First Key as our consultants turned out to be a very wise decision. It’s one thing for somebody to put a quote in front of you for what you need and what’s going to happen, but it’s another thing to understand all of the parts and bits and pieces and the system. First Key has been extremely beneficial to help pull the project together and keeping it moving forward.”

First Key’s Gerhart was immediately intrigued. “At First Key we work on a lot of breweries from new construction to expansions and operating improvements, but it was a truly unique and rewarding experience for me to work with a brewery with deep historical roots and connection with its community.”

“This is a very unique project,” Zwicker agreed. “We do basically 100 thousand barrels a year. We’re building a new brewery 18 miles away, and our beer is currently contracted out of Latrobe. So it’s a very unique puzzle to pull all of this into one house. It’s a struggle. The supply chain with the different breweries, the different personalities, different people.”

When it came time for the hands-on part of the task to begin, all of those conceptual challenges soon became tangible. One portion of the building had a substantial coal fire burning underneath it, necessitating its demolition while the fire was put out at the same time. For the bulk of the building that remained, every bit of brick was sandblasted and coated, every inch of steel was repainted, and every window was replaced. The plumbing and electricity had to be redone. Walls had to be torn down, while new walls had to be added. In order to put the tank farm inside, floors were removed, creating a vast open space.

The team has worked together in what First Key’s Gerhart calls “a fantastic dynamic.” “If we have any roadblocks, Todd helps clear them for us.” Of Gerhart, Zwicker says “He knows exactly what he’s doing, how to put the brewery together. He doesn’t step in it or fight his way through it, he knows the nuts and bolts of the full circle.

While Gerhart and Zwicker are both quick to credit one another, each reserves the ultimate credit for Forrest, who “beats that drum from the top down” according to Gerhart.

Cliff Forrest likes to keep a low public profile, but his leadership style has kept him highly visible to the team during the entire project. As Gerhart pointed out, “Cliff and I talk regularly on the phone. He’s at the plant quite often checking on things.”

Everyone involved with the project talks about the buzz it’s created in the larger community. “There’s just a lot of excitement – the word spreading around Pittsburgh about our new facility,” said Rachel Semelbauer, the company’s marketing coordinator. “People are excited about getting our brewing back.”

Gerhart, too, was struck by the level of enthusiasm in the community. “When you tell people you’re working on this project everyone gets immediately excited. They have a boatload of questions and nothing but heartfelt praise for the project, how excited they are to see this community be on the rebound.”

That excitement started translating into sales results while the actual rehabilitation of the physical facilities was barely underway. “The brands skipped multiple generations, so you have a very young audience that’s taking up the brand now,” explained Zwicker. “There are obviously seasoned Pittsburgh Brewing drinkers, but you also have young adults right now that are drinking our brands that had probably never even considered drinking them.” One constant throughout tough times and good times has been the brewery’s sponsorship of the Penguins, Steelers, and the Pirates. “We’re supportive of our hometown region, that’s probably the biggest thing right there. We’re involved with all the sports teams, the university of Pittsburgh, we have a lot of advertising we do in the Pittsburgh market. People see that, they want to be part of that.”

The new facility shipped its first barrel of beer in June of this year. But the physical transformation of the entire complex has only just begun. “There’s a lot of green space up there to do almost whatever we want,” Zwicker pointed out. With further support from First Key, installation of a 10-barrel brewery for innovation and new product development is underway, and an old boiler building from the PPG days is being rehabilitated and transformed into a distillery. A new outdoor stage and event venue will be adjacent to that. Additional plans under development include a restaurant/taproom, a museum, a brewery store, and reinvigoration of the property’s marina – not to mention additional capacity, raising the total to 300,000 barrels in the second phase and 600,000 in the third.

Tours will soon be offered, launched from the mezzanine overlooking the tank farm. “We’re trying to make it a destination, on the order of Sierra Nevada,” said Semelbauer. “Not just ‘We’re going to a brewery,’ but ‘We’re going to the brewery and we’re going to have dinner and go on the tour.’ ”

Pittsburgh has gotten its brewing back – in a bigger way than anyone could have imagined just a few short years ago. No one with a stake in the project, including the Western Pennsylvania beer-drinking community, doubts that the impressive new facility will generate plenty of excitement and delicious beers for years to come.

By Mike Kallenberger